|

| The Anti-Slavery Society Convention of 1840, painted by Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841. |

Alyssa Bellows, “Evangelicalism, Adultery, and The Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 62.3 (2020): 253-74.

For readers not familiar with the life and achievement of Harriet Jacobs (1813/15-1897), could you give us a brief biography?

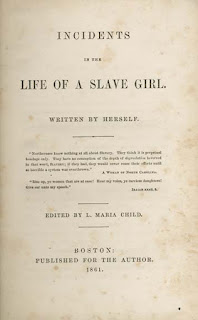

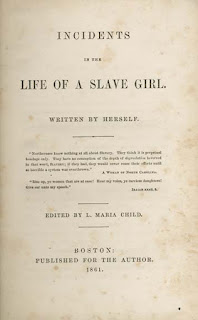

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in North Carolina where she lived until she escaped north in 1842. She is the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself (1861), the first published autobiography written by a slave woman.

As she reports in Incidents, her master, James Norcom threatened her sexually when she was a teenager. To reject his unwelcome advances, Jacobs began a sexual relationship with another white man and eventually bore two children. When Jacobs learned that Norcom intended to send her children away from the town and out to the plantation where they would likely be abused, she immediately took action by running away. She reasoned Norcom would not move her children as long as they might serve as bait to recover her. She remained nearby, however, hiding in a crawl space in her grandmother’s home and near her children while Norcom searched the country, following false leads and even letters carefully planted by Jacobs. Finally, after nearly seven years of living in the small attic cubby, Jacobs made good her escape. For ten years she lived and worked in Boston and New York until her freedom was purchased in 1852. During this time she was reunited with her children who had also been emancipated. She worked on writing her narrative during the 1850s and published it pseudonymously in 1861.

During and after the Civil War, Jacobs worked in relief missions and humanitarian efforts in the south before returning north and working with her daughter.

|

| Harriet Jacobs’ only known formal portrait, 1894. |

During her time of enslavement, Jacobs had decided to escape and spent the next seven years in hiding, separated from her children. Considering the stifling conditions of her hiding places, what was this period of her life like for her?

Jacobs reports that the garret where she remained hidden for almost seven years was nine feet long, seven wide and three high: “the slope [of the roof] was so sudden that I could not turn on the other [side to sleep] without hitting the roof” (I, 128). Extreme heat in the summer, cold and even frostbite in the winter; rats, mice, and insects her frequent companions; total darkness, stifling air. Her grandmother, uncle and aunt would chat with her at night when they could; Jacobs bore a small hole from which she occasionally got her eye on her children as they grew up below. For exercise, she crawled back and forth. On the handful of occasions that she left the garret, the physical exertion was so great she could hardly return to her hiding place. Later, while writing Incidents, she reveals that “my body still suffers from the effects of that long imprisonment, to say nothing of my soul” (I, 166).

In addition to these forms of confinement, Jacobs suffered under the emotional and psychological stress of her family in jeopardy. When she first disappeared, her uncle, brother and children were jailed in the hopes that they would betray her (even though they didn’t know where she was). Her grandmother fell ill (and recovered). Her master threatened to sell her children and even when they were bought by their father, she still could never trust that he wouldn’t decide to sell them elsewhere.

Her story is nearly unimaginable; at least, for my part, I cannot see myself surviving as she did. This may be one reason her story was thought to be fiction for so long. During her lifetime, Jacobs was the recognized author of Incidents; but it’s worth noting that until Jean Yellin Fagin authenticated her account in the 1980s many later readers and scholars believed Incidents was written by Jacobs’s editor, Lydia Maria Child. Child was an author in her own right and helped Jacobs organize her material. The theory lasted in part because Jacobs used a pseudonym and fictionalized all the names and places in her autobiography and perhaps because Jacobs’s perseverance in the loophole was too fantastic to be believed.

What’s really striking to me, however, is that even though she mentions all the details I’ve recorded above, they are only the backdrop to the story and events unfolding outside her crawl space. She is always thinking more about those outside, especially her children, than herself.

|

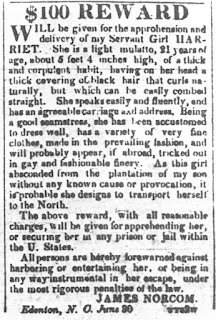

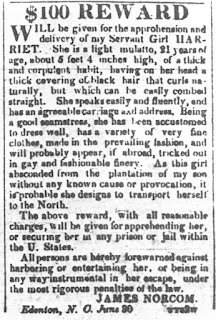

| Ad for the capture of Harriet Jacobs. |

Tell us a little bit about the Rochester Reading Room and Jacobs’ relation to it.

Rochester probably doesn’t register with many people outside New York, except perhaps for its annual snow totals or as a pitstop on the way to Buffalo and Niagara Falls; but in the early nineteenth century, it was a hub for women’s rights and antislavery activism. Rochester was a place where conventions were held, speeches were made, and speaking tours began. John S. Jacobs, Harriet’s younger brother, escaped from slavery as well and he quickly became involved in antislavery. He proved to be a forceful and militant speaker, traveling circuit with the likes of Frederick Douglass who had escaped around the same time. John organized and directed the Reading Room but when his sister arrived in Rochester in 1849, he asked her to oversee it as he was out of town for extended periods of time for speaking engagements. The Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room was located in rooms over those housing Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star, and it was dedicated to “latest and best works on slavery and other moral questions” (Yellin, Harriet 103). We don’t know the full extent of what texts were housed in the reading room but from a weekly advertisement John ran in The North Star for nineteen weeks starting in March 1849 we know that there was great variety in genre, from young adult literature to sermons to Pillsbury Parker’s treatise, The Church as it is, to a fictional slave memoir by Richard Hildreth, The Slave; or, Memoirs of Archy Moore. The Reading Room only stayed open about a year, but it was during that time that Jacobs started seriously thinking about writing her own story, and experimenting with telling it to her friends in Rochester.

|

| Harriet Jacobs’ antislavery reading room in The Talman Block, the same building in Rochester where Frederick Douglas had his newspaper office, 1849. |

What evidence is there for her engagement with texts there?

We don’t know much about how she spent her days in the Reading Room. Jean Yellin Fagin, Jacobs’ biographer, suggests that she spent her summer reading her way through the texts as she helped visitors (Yellin, Harriet 103). This makes sense to me, as I argue we can trace a number of intertextual fingerprints between the texts of the Reading Room and Incidents. For instance, Jacobs’ call for “missionary work” among the slaveholders continues an argument begun by Pillsbury Parker in The Church as it is (I, 82; Pillsbury 25-27). She also uses phrases found in the texts, like “doctors of divinity,” a sarcastic dismissal of learned men who nevertheless can’t see the simple importance of abolition (I, 82; Pillsbury 11). One final example, Jacobs calls the Posts “practical believers in the Christian doctrine of human brotherhood” (I, 211). Her words recall Theodore Parker’s sermon in the Rochester reading room urging Christians to look beyond “doctrines of the sects” to “the most important practical doctrine of Christianity”: “LOVE TO MEN” (Theodore Parker, A Letter to the People of the United States Touching the Matter of Slavery (Boston: J. Munroe, 1848): 70).

There are, however, more interesting stakes here than simply parallel phrasing. Jacobs started writing Incidents during that summer in Rochester while she was working in the Reading Room. And so we can ask ourselves: how did she become a writer? How do any of us become writers? How do we practice and cut our teeth and experiment and learn? And this is where I think the Reading Room really becomes central to Incidents. I like to imagine the Reading Room as a Writing Room for Jacobs. For instance, I see the influence of genre between the Reading Room texts and Incidents. Many scholars have noticed the parallels and departures from sentimental literature that Jacobs expertly invokes and reworks (see Thomas Doherty, “Harriet Jacobs’ Narrative Strategies”). But I argue that the context of the Reading Room should expand our awareness of the many genres Jacobs juggles in her narrative. The fluctuations in tone and voice in the narrative capture the variety of genre writing available in the Reading Room. I didn’t go into this in my article because it’s really just a speculative pet theory of mine; but I like to imagine Jacobs training herself in the Reading Room, seeing what kinds of rhetorical and literary strategies were being practiced and published and then trying them out for herself. This is such an excellent writing practice for anyone just starting out and I think it shows great maturity in dedication to learning a craft. It tells me she was seeing herself as a publishable author, not just keeping a diary for posterity; that she was conscious of her reader in a way far beyond wondering what they might think of her sexual experiences. I would argue that her experiments with genre and voice show her more in control of her writing than she is sometimes given credit for in a typical reading that sees her as struggling to appease or defer to her audience. But – this all assumes, of course, that my speculation is correct and that Harriet Jacobs was, in fact, not only reading her way through the Reading Room but also writing her way through it.

|

| Frontispiece for Incidents in the Life of A Slave Girl. |

The Bible seems central to Jacobs’ reading and writing. What Biblical passages or stories were especially important to her?

She mentions so many it’s hard to pick just one. It’s obvious to me from the variety of allusions to both Old and New Testament texts that she was familiar with the Bible from cover to cover. If I had to pick just one, I would say “But the LORD said unto Samuel, Look not on his countenance, or on the height of his stature; because I have refused him: for the LORD seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the LORD looketh on the heart” (1 Samuel 16:7, KJV). It’s the text alluded to by the one sympathetic clergyman Jacobs meets in the South.

Jacobs rarely quotes full-length or direct verses from the Bible. Instead, she weaves together biblical allusions and her own phrases of biblically-inspired language. For example, consider this excerpt from a letter to her friend, Amy Post, in 1862:

the good God has spared me for this work & the last six months has been the happiest of my life. sometime my sky is darkened but my faith in the omnipotent is strong – our prayers & tears have gone up as a memorial of our wrongs before him who created us – and who will judge us – Man may desire to stand still but an arm they cannot repel is leading them on – they may stop to worship the Idol that is making desolate their hearthstones a just God is settleing [sic] the account. (Jacobs, Family 427)

Yellin calls this letter Jacobs’ most personal: “Jacobs would write a great many letters over the next four years… But in no other letter that has been found would she permit herself such a personal expression of feeling” (Yellin, Harriet 163). The metaphor of the memorial offering and ambiguous reference to the idol “making desolate their hearthstones” interject Biblical language transformed into personal metaphor. Those phrases aren’t taken directly from the Bible but they do modify and adapt similar sounding passages, such as Psalm 56 which describes how God collects all the speaker’s tears into a bottle. Jacobs’ conception of deity in the letter ranges from the benevolent providence of the “good God” to the “just God” holding slaveowners accountable to a creator God who listens to “prayers & tears.” Perhaps most intriguing, the synecdoche of God as an arm configures God as both figuratively impersonal yet actively involved in human affairs. This deeply theological letter consolidates the many textures of Jacobs’ patchwork God, a God pieced together from varied experiences with US Protestantism, and yet one fueling the inertia of her energetic dashes. Significantly, this letter seems concerned just as much with who God might be, whether creator, sustainer, or judge, as with what such a God might accomplish in the world. This letter, then, captures Jacobs as a theological and biblical thinker; the rhythms and diction of the Bible saturate her writing even when she isn’t alluding or quoting directly.

|

| Grave of Harriet Jacobs at Mount Auburn Cemetery, Massachusetts, 2008. |

Where might we see biblical discourse in contemporary US politics? Does it gravitate to one party or the other?

Ooh I love this question. This is something I’ve been pondering over for ten years or so. Very briefly, I’d say that yes, we see biblical discourse in contemporary US politics all the time and on both sides from both Christians and non-Christians. Progressives lean toward so-called “social gospel” texts like the sermon on the mount (“Do not judge”) and themes like love, caring for the poor and mercy. Conservatives gravitate toward Psalm 139 (“I am fearfully and wonderfully made… You knit me together in my mother’s womb”) and themes of truth, right living, and hard work. Surprisingly, this past year I have heard friends from both sides, some religious, some not, using the account of Jesus cleansing the temple (found in all four gospels), although to different ends (conservatives pointing out his “zeal” for the church and liberals pointing to his activism and violent overthrow of greed/consumer culture).

To me, the most salient point to make here is that both sides fall into the same error. In most cases, right or left, Christian or non-Christian, when scripture becomes a political tool – and, more specifically, as a political tool meant to humble or correct someone from a different political circle – you are missing the whole point. Many times in the gospels we see people trying to get Jesus to claim the “red” or “blue” choices of his time but he always responds radically aside from their expectations. When politics come up, he consistently makes everybody mad or astonishes them by being non-partisan, whether you were a nationalist Zealot or a cosmopolitan tax collector or an academic Pharisee. As anyone knows who has tried to do this today in the US, being non-partisan without apathy is nearly impossible and a very lonely road.

And yet he also is the example par excellence of bringing people together: at the last supper we find Matthew the tax collector (a flunkey for Rome) sitting and breaking bread with Simon the Zealot (a Jewish nationalist). And you thought Thanksgiving and Christmas were tough this past year! These were the most partisan positions of that time and place but Jesus teaches them to be brothers. So biblical discourse, rightly used, should never be about shaming the other side or preaching to the choir (no churchy pun intended). Biblical discourse is, to the contrary, for self-reflection, humbling and repentance, and correction that defies partisan politics in favor of family, justice and healing. To my mind, the onus is really on US Christians to change their patterns of using biblical discourse inappropriately.

To bring this question back around to Jacobs, something that strikes me as interesting is that even though she starts from a political position (abolition) and even as she uses biblical discourse to rebuke and correct her readers, she’s not just quoting the scriptural clichés of the day. The key seems to me to be her breadth and depth of reference to biblical discourse. It’s obvious to me that, unlike most Americans today, her biblical literacy is very high. She successfully uses scripture, therefore, to parse a political topic (that is, emancipation, anti-racism) precisely because she is attuned to the big picture and is relying on so many different passages. She is the antithesis to today’s trend of quotable, decontextualized scripture sound-bites like “God is love.”

|

| St. James Church, built in 1889, Massachusetts, 2012. |

In Incidents, Jacobs uses the Bible and its doctrine to communicate. What “shared text,” if any, is available today?

This is such an interesting question and much tougher than I first thought. Because I want to expand what we mean by text, if I may. In the nineteenth century, a writer could allude to the Bible, even loosely, and trust that readers knew the biblical text well enough to identify and place the allusion. That is certainly no longer the case today as most non-Christian readers may never have read the Bible; even many Christians today have never read the Bible in its entirety. And I don’t think we have any shared text today that we can collectively reference the way readers could in the nineteenth century. So I would offer a tangential cultural substitute, “social media.” It so permeates our lives and conduct, emotions, relationships and so on and we all “know” it so well that we can speak about it without fully explaining ourselves. We might say, “Well! That’s social media for you!” And depending on the context, everyone gets it. Or, “We all know what social media’s like, after all!” And we do! People manipulate social media, mobilize it to their cause and so also with the Bible on both sides of the antislavery debate. So for our cultural moment, I think social media fills a similar cognitive space to that held by the Bible in the nineteenth century. But really, it’s significant that we have no modern equivalent to that shared text. It boggles my mind that scholars of the nineteenth century do their work without getting to know the Bible when it functioned in that pervasive way.

|

| American Equal Rights Association Memorial, 1867. |

Parker Pillsbury (1809-98) was known for his role as a progressive social reformist, helping to draft the American Equal Rights Association constitution and supporting the idea of land redistribution for the freed slaves. Does his work and advocacy continue to shape modern efforts for reform?

Certainly, I think we could tie current reparations activity to Pillsbury as the kind of legacy he was hoping to inspire. Pillsbury was a Garrisonian comeouter: frustrated with the lack of support for antislavery among churchgoers, he joined with abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and defected from church-based reform in favor of politics and secular organs of change. Historian John McKivigan notes that most scholars have interpreted Garrisonian comeouterism, a turn to politics, as a decline in church action; however, McKivigan argues that during the 1850s, varieties of comeouter sects developed within Christian circles. From denominational schism, Evangelicals founded new churches committed to “vigorous” antislavery reform (McKivigan 237). In Rochester, Jacobs’ friends, Amy and Isaac Post, belonged to just such a group (Yellin, Harriet 101). This Quaker comeouter sect maintained “close ties” with Garrisonian comeouters, appealing to both religious and secular platforms (McKivigan 249). And Pillsbury, obviously, remained closely tied to the US Church by writing to and petitioning Christian readers to support antislavery and seek racial equality. So even closer to the mark would be the variety of reparations being carried out by US churches. There are a number of older, “mainline” denominations, particularly Episcopalian churches, that have dedicated significant financial aid as well as made statements of confession and repentance for actions connected to slavery and racism in their pasts. The Episcopalean Dioscese of Texas, for example, is committing 13 million dollars in reparations for scholarships, aid to historically Black churches, and other reparations.

|

| Coloured School (historical designation) in Alexandria, Virginia, taught by Harriet Jacobs and daughter agents of New York Friends, 1864. |

Jacobs’ is one of the few autobiographies that we have from a former female slave. What difficulties or reservations might she have had about sharing her story that a former male slave might not have had?

Obviously, the first concern for Jacobs was telling of her sexual harassment, illicit sex, and her illegitimate children to an audience that expected women to remain chaste, modest and “delicate” in regards to sexuality. Nearly every scholarly article on Incidents touches on this aspect of her narrative and Amy Post’s description of Jacobs’ initial recounting makes clear the great difficulty and trauma she experienced retelling her story. However, I would also like to suggest that this question perhaps too simplistically assumes the binaries we assign to slave narratives based on the gender of the author. Male slaves were sexually exploited as well. Jacobs even tells of a slave named Luke who was horribly and almost continuously beaten by his master and subjected to “freaks of despotism.... of a nature too filthy to be repeated” (I, 214). Or as she records the nightly patrol of the overseer, entering every cabin “to see that men and their wives had gone to bed together” (I, 55). I think we should assume sexual trauma rather than not as the baseline slave experience. I think the difference for Jacobs, and perhaps for any former female slave, is the presence of her children: her sexual trauma, especially as transformed by motherhood, is the plot, the motive for escape.

|

| Former home of Harriet Jacobs, located at the corner of Story St and Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2008. |

Why use the pseudonym “Linda Brent” in publishing Incidents?

In her preface Jacobs explains that she “concealed the names of places, and [gave] persons fictitious names. I had no motive for secrecy on my own account, but I deemed it kind and considerate towards others to pursue this course” (I, 3). Needless to say, not all critics have taken her at her word. There are a variety of reasons Jacobs chose a pseudonym, such as protecting herself from censure, particularly as she nannied for a family that was well-connected in literary and social circles. Some critics have surmised that Norcom did violate Jacobs and that by choosing a pseudonym Jacobs could alter those details of her narrative more easily. Saidiya Hartman reads the text’s various circumlocutions as evidence that “seem to make escape [from sexual violence] impossible” (Scenes, 107). P. Gabrielle Foreman goes so far as to argue that, contrary to what she terms Linda’s “principle script” of “sexual ‘triumph,’” Jacobs experienced sexual violence in the form of rape by her master, Dr. Norcom (“Manifest in Signs: the politics of sex and representation in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” in Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: New Critical Essays, ed. Deborah M. Garfield and Rafia Zafar (New York: Cambridge UP, 1996): 83-84).

Although she has only been fully recognized as the author of Incidents since 1987, Jacobs was received as the author in her own time. She was respected for the work, especially in antislavery circles (Yellin, A Life 161). Jacqueline Goldsby describes the pendulum of critical reception between too little trust in veracity at first, too much emphasis on documentation now; she pitches the conflict between history and “narrative imperatives of literature” arguing that we must recapture a sense of the literary for Incidents (Goldsby 14). Jacobs may have felt this tension in composing her narrative. Jennifer Greeson describes the ways Incidents blends sentimental convention (using the third person), urban gothic and the slave narrative (using first person), yet another mark of her sensitivity to genre (289-290).

In my opinion, Erin Forbes has the most interesting and unique read of the relationship between author and narrator among the scholarly essays that I’ve read. She draws out the Spiritualist influences in Incidents to argue that Jacobs “envisioned her authorial power as the limited yet radical agency of the medium, who communicates as and for another” (479). I don’t find enough Spiritualist material in Incidents to think that it had much personal significance for Jacobs (as opposed to the numerous allusions to biblical language) but as a matrix and theoretical development for understanding black subjectivity I think Forbes unites graceful articulations with hard-hitting insights.

|

| View of the city of Boston, painted and engraved by Robert Havell, 1841. |

What role should this choice play in our understanding of its legacy?

Jacobs’ use of the pseudonym has generated interesting analysis of the relationship between its author and narrator but also challenges critics in their articulation of “Jacobs/Brent” (Forbes, “Do Black Ghosts Matter?” 459). Hazel Carby, for instance, decided that “the author will be referred to as Jacobs, but, to preserve narrative continuity, the pseudonym Linda Brent will be used in the analysis of the text and protagonist” (Reconstructing, 47). Since Yellin’s authentication of the text in 1987, scholars have generally accepted the text as Jacobs’ memoir though Foreman warns against the critical tendency to “accept the transparency” between Jacobs and Linda (“Manifest in Signs,” 83). Foreman believes that Linda’s sexual harassment does not fully tell what Harriet Jacobs experienced in slavery.

I primarily treat the author and narrator as Harriet Jacobs. Doing so honors the fact that Incidents is a memoir and not a fictionalized account. Also, my article focuses on social and cultural referents that were obviously of meaning to the real Harriet Jacobs rather than relevant to a narrator. However, if my thesis had been more concerned with either formal or psychological questions than I would have examined the relationship between Jacobs and Brent or “Jacobs/Brent” more rigorously. In other words, I don’t think there’s necessarily a one-size-fits-all or “right” answer here. It all depends on what point one is trying to make and whether or not analysis of the narrator as Brent lends signifying insight to one’s argument. Personally, as I said, and in terms of legacy, I think it’s important to emphasize Jacobs over Brent simply as a nod to her undisputed authorship. And, especially in terms of religious discourse, since Jacobs used a very similar voice in her letters and we have newspaper notices that she opened conventions with public prayer and so on, it makes sense to me to see those kinds of declarations as belonging to Jacobs and not only the fictional narrator.

|

| St. Paul’s Church where Harriet Jacobs and her children were baptized, North Carolina, 1937. |

Jacobs is very open about her experiences with sexual violence. From where do you feel she gained the strength to continue pushing on in life, even after such exploitation?

The answer is undoubtedly her children. She described her perseverance in the attic crawlspace this way: “My friends feared I should become a cripple for life; and I was so weary of my long imprisonment that, had it not been for the hope of serving my children, I should have been thankful to die; but, for their sakes, I was willing to bear on” (I, 141). Many scholars have written on her role as a mother and the importance of her children. Of course, her maternal sentiments were likely to humanize her with her audience and create sympathy but Jacobs returns again and again to the welfare of her children and it’s possible to read Incidents as just as much about them as anything else. The decisions she makes and the actions or precautions she takes always go back to her children. I was struck rereading it for this interview just how frequently she interjects wishes and blessings for them, sorrow at not being near them, and avid descriptions of her mother’s heart. It’s really how she saw herself, as a mother first. Hazel Carby believes Jacobs’ children were a particular source of strength for her as an author uncertain of her reception for the “motherhood that Jacobs defined and shaped in her narrative was vindicated through her own daughter, excluding the need for any approval from the readership” (61).

|

| Emancipation Proclamation, by E.G. Renesch, 1919. |

The ending of Incidents delivers a “a happily ever after.” Do you think the freedom of a slave needs to be included in order for the narrative to be effective?

I’d actually like to modify the question here because I suppose it depends what you mean by “happily ever after.” Yes, there is the fact of her freedom. And yes, she ends by imagining memories of her grandmother “like light, fleecy clouds'' providing solace (I, 225). But taken as a whole, I find the ending of Incidents distressed and even depressed. Consider her final words: “I would gladly forget [the dreary years I passed in bondage] if I could. Yet the retrospection is not altogether without solace; for with these gloomy reflections come tender memories of my good old grandmother, like light, fleecy clouds floating over a dark and troubled sea” (I, 225). The uplifting platitudes cannot hold back the truth. The ambiguous restlessness of these closing lines attempts to push away darkness by grasping at memory and light but ultimately Jacobs herself is the dark and troubled sea. Her everyday state beats to the crush of turbulent waves, not the memory of solace that only floats above. This poignant imagery pulls Jacobs not only down from the clouds but into the choppy waters of the middle passage. There’s such an historical imagination in these few words and it carries the burdens and bitterness and pain of generations. So yes, she is free – but is that all that is required for happiness and healing?

Even the actual moment of her freedom rings hollow. Hearing the news, her “brain reeled... Those words [bill of sale] struck me like a blow. So I was sold at last! .... much as I love freedom, I do not like to look upon [the bill of sale]” (I, 223, emphasis original). She feels she should rejoice, celebrate, feel gratitude but to feel all of these things for the sake of freedom means feeling all of these things in the context of being bought and sold. That’s a double-edged sword: she can never celebrate the one without remembering the other. And so her freedom is always shadowed by this knowledge of its literal cost. I read all of Incidents, but especially her final chapter, as being deeply touched by this tension. There is no pure happiness here. Relief and some security, perhaps, but more bitterness than happiness.

In light of this recontextualization I would say, yes, I think the freedom of the slave needs to be included for the narrative to be effective. Not to fulfill the reader’s desire for resolution but to understand what freedom means for the former slave, to take on board that freedom comes burdened and gloomy not bright and rewarding. So it also depends on what the question means by “effective.” It’s the unexpected pain of freedom that should shake up readers, especially today’s readers who might be hoping for endings or working towards resolution to race relations in the US and Jacobs is warning us: it’s just not that simple.

|

| Statue of Liberty facing Manhattan during an incoming storm, New York, 2006. |

What are you currently working on?

At the moment, I am not working on anything! I am a stay at home mom, which I absolutely love. I know I should probably craft some kind of hypothetical book project to make myself sound more professionally involved but that wouldn’t be the truth. And I think Harriet Jacobs would encourage me to both tell the truth and to embrace and cherish every moment I have with my two children, similar in age to her own when she could only watch them occasionally through a one-inch peephole.

No comments:

Post a Comment