By Alexandra Steele

John G. Peters, “Silence, Space, and Absence in Joseph Conrad’s African Fiction,” TSLL: Texas Studies in Literature and Language 63.4 (2021).

|

| The Joseph Conrad, Mystic Seaport (2011); photo by olekinderhook, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported |

Joseph Conrad is more often mentioned than read. What things help to explain this?

This is true to a certain degree. Heart of Darkness I think is read regularly in classes, but less so Conrad’s other works, ones that in the past were regularly studied. This is likely a product of two factors. First, with the broadening of the literary canon, there are simply more works to choose from than in the past. Second, Conrad is a product of his times and he (and his narrators) sometimes express views and language that would not be appropriate now. Also, Chinua Achebe’s famous article, “An Image of Africa,” criticizing the racial views and portrayals in Heart of Darkness has probably contributed to this trend as well.

|

| Chinua Achebe speaking at Asbury Hall, Buffalo, as part of the “Babel: Season 2” series by Just Buffalo Literary Center, Hallwalls, & the International Institute. Photo by Stuart C. Shapiro, reproduced under the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 |

For readers not familiar with his works, could you give us a short list of his best writing—perhaps in the order we might work our way through him?

I would suggest the following: Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim, Nostromo, The Secret Agent, Under Western Eyes, “The Secret Sharer,” “Youth,” and Typhoon, in that order. There are, of course, other valuable works, but these are I think his best.

|

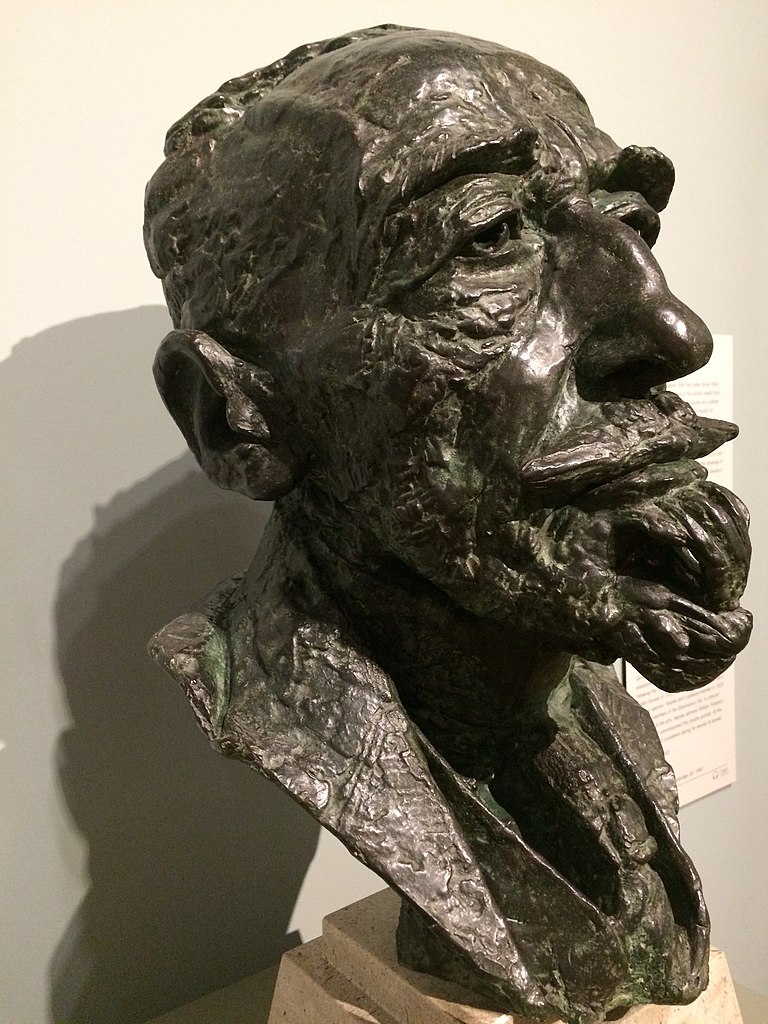

| Bust of Joseph Conrad, by Jacob Epstein, 1924, at National Portrait Gallery, London |

What should we know about Conrad before starting his works of fiction?

Conrad is a difficult writer. His skepticism, world view, and the moral dilemmas in his works contribute to this difficulty. In addition, his narrative experimentation adds strongly to the difficulty in approaching his works. Of course, some works, like Typhoon and “Youth,” are fairly straightforward narratively, but many others present significant challenges to the first-time reader. For example, there is one chapter in Lord Jim where it is impossible for the first-time reader to have any real idea what is going on because the narrator, Marlow, is telling his tale to a group of listeners who have much more knowledge of the events than do first-time readers.

|

| Mr. Joseph Conrad |

Do you have any favorites among his works, either on or off the list you shared?

This is a somewhat difficult question because several of his works (in particular Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness, Nostromo, and The Secret Agent) have different aspects that recommend them. If I had to choose one particular favorite, I suppose it would be Heart of Darkness.

Unsurprisingly, Conrad’s work is often polarizing. In an era of heightened sensitivity to issues of race-based injustice, what specific value do you believe texts like Heart of Darkness and “An Outpost of Progress” hold?

“An Outpost of Progress” is a somewhat straightforward, anti-colonial text, and that aspect I think lets modern readers know that there were works written at the time (not many) that were critical of Western imperialism. Heart of Darkness expresses a similar sentiment but is a much more complex work, dealing also with a journey into the self and investigating such questions as the nature of the universe, the nature of knowledge, and the nature of human existence. Although both works express sentiments that would not be considered appropriate today concerning race, I think they can be seen as measuring devices as to how race was viewed historically as opposed to today. In short, I think we can learn where we used to be with such questions, where we are now, and where we need to go in the future.

|

| Imperial Federation map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886, reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic |

Is there a text you see as the antithesis of Conrad in terms of sound and space? That is, someone—perhaps from approximately the same era—whose works are the antithesis of Conrad’s?

Given my argument concerning Conrad’s ultimate conclusion that the West is a metaphysical void (its empty space being emblematic of its cosmological emptiness), I think that most of the writings of the turn of the 20th century (Conrad’s most productive period) would run counter to Conrad’s views. I’m thinking specifically of works such as John Galsworthy’s The Man of Property or H. G. Wells’s Tono-Bungay or George Gissing’s The Odd Women, that is those works that extended the Victorian novel of social conscience (as opposed to the Modernist world view that Conrad posits). These authors were excellent at their craft, extremely popular, and well thought of in the literary world of the time, but underlying all novels of social conscience is an essential affirmation of society. They certainly identify social ills, but their assumption is that if such ills were cured, society would be a better place and that we can get there because ultimately society is based upon transcendental truths. This latter idea is precisely what Conrad rejects (as did so many other Modernists). Conrad, who was good friends with H. G. Wells for about a decade, had a falling out and is reputed to have once said to Wells something to the effect, “The difference between us is that you hate humanity but think they can be improved, while I love humanity but know that they cannot.”

|

| Joseph Conrad signature (1922) |

What about his work is of particular interest to you?

I have always been taken with the moral dilemmas Conrad’s characters encounter and how they seek to create meaning (contingent not transcendental) for themselves in the face of what they see as an empty universe. I also find his narrative experimentation to be an outward manifestation of this world view.

How has the reception and criticism of Conrad changed during your academic career?

As pointed out in question #5, there is a good deal more emphasis on Conrad’s cultural blind spots now than there once was. Despite what seems obvious to modern readers (the issues of race and colonialism in his works), it wasn’t until the late 1940s (a Marxist-influenced reading of Nostromo) that anyone even talked about these issues, and it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the topic became a prominent interest of scholars. Of course, that was before my time really. The major shift I have seen personally has been I think the same shift in the reaction to most authors, that is considerably greater emphasis on issues outside the literary text itself, particularly focus on social and cultural issues, whereas when I was a beginning scholar, the primary commonality among most approaches to Conrad (and other authors) was an emphasis on the text itself.

| Joseph Conrad (1904) |

What parts of Conrad’s achievement hold up in 2021, and what elements have faded into obscurity?

I think Conrad’s works have a flexibility or complexity to them that has kept them current. Scholars interested in colonialism, culture, environmentalism, psychology, gender, and narrative (areas of current interest), for example, will all find fruitful areas to mine. It seems that whatever approach to literature has been current ever since Conrad was writing, scholars have been able to find in his works things worthy of study. As for what may have faded into obscurity, I suppose Conrad’s investigation into an empty universe and the human response to this phenomenon is something that does not have the same interest for scholars that it once had (although I deal with this issue in my article and still find it to be a valuable topic to investigate).

|

| Joseph Conrad signature (1925) |

Like many modernists, Conrad is not particularly sympathetic toward women. Does this enhance or detract from his arguments that there is little separating the civilizations of Europe and Africa?

As a product of a time that saw distinct gender hierarchies, I think that such hierarchies have been seen to have existed across cultures of that period, so in that sense there would certainly be little separating civilizations of Europe and Africa it would seem to me. Conrad’s portrayal of women has often been seen to be limited. As early as Grace Colbron’s 1914 article on the topic, this limitation has been discussed. Conrad does have some sympathetic portraits of women in his works, such as Emilia Gould in Nostromo, Winnie Verloc in The Secret Agent, and Natalia Haldin in Under Western Eyes, and Nina Almayer in Almayer’s Folly. But invariably such figures (with the exception Nina Almayer) have little if any power to effect social change or even significant change in their own lives, and in their affirmative qualities, they often exhibit elements of the “angel in the house.”

Silence seems key to Conrad’s sense of place and meaning. What is Conrad himself silent on and how might those omissions contribute to our understanding of his work?

Silences, both literal and metaphorical, permeate Conrad’s works, and these voids or omissions point to his view of the nature of the universe, but the also point more specifically to the nature of knowledge, contending, in various ways, that it is impossible to know anything with certainty. For Conrad, the best one can do is an approximation rather than certainty.

|

| Photo by Piotrus, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported |

Say you teach a class where Heart of Darkness and “An Outpost of Progress” are central texts. What other works of fiction would you want to incorporate into the semester and what would you title the class?

In such a class, assuming that it were limited roughly to the historical period of those pieces, I would look to include other texts set in the colonial world. Many of Kipling’s texts, such as Kim or “The Man Who Would Be King,” would be appropriate, particularly as a counter to Conrad’s views. Other works might include E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Conrad’s Almayer’s Folly, and perhaps works from the particularly popular vein of colonial fiction such as H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines or She. In each instance, a different response to colonialism and the colonial world arises.

|

| Photograph of Nobel Laureate V. S. Naipaul, speaking in Dhaka, Bangladesh, photograph by Faizul Latif Chowdhury, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International |

In your opinion is there a current-day Heart of Darkness already written or filmed, or has culture moved on from this particularly problematic portrayal of race?

I’m afraid that I am not well versed in contemporary film or fiction, so it is difficult to say. V. S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River has often been seen to be in some ways a response to Heart of Darkness, and there have been some African writers who have also written responses to the novel, although I have not read those works myself.

What are some of the most successful film versions of Conrad’s writing? Conversely, which films have failed? Do the respective successes and failures of adaptations tell us anything about what his works are, at base?

Probably the most successful adaption of Conrad’s works to film has been I think Apocalypse Now. Despite the different setting, the film does a good job of translating the essence of Heart of Darkness (except that the Marlow figure in the film is a less sympathetic character). Some years ago, TNT did a version of Heart of Darkness, featuring John Malkovich as Kurtz, but I personally thought it quite bad. Around the same time, a mini-series was done of Nostromo, but it seemed to confuse the time shifts in the novel unnecessarily, I thought. A prominent film version of Lord Jim was done in the 1960s, but its primary problem was its failure to translate the significantly conflicted view of Jim that appears in the novel. In the 1970s, Ridley Scott did a film version of The Duel (titled The Duelists), which I thought was quite successful. The fact that so many film versions (and there have been many others) have not typically been successful I think tells us that it is very difficult to translate the moral, cosmological, and narrative complexity of Conrad’s works into film. Although film is very different from the stage, it is probably worth noting that Conrad’s himself attempted to adapt several of his works to the stage, but they were all largely unsuccessful.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on what I hope will be a book on Conrad and silence, tentatively titled Joseph Conrad and the Silence of Modernism. The TSLL article will form part of one of the chapters. The book looks at such silences as spatial silence, narrative breaks by Conrad’s narrators, the inadequacy of language, and narrative and epistemological barriers between original events narrated and what the reader eventually receives.

| ||

| Stamp of Belgian Congo (1909) |

| www.utexaspress.com |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(LOC)_(15356484611).jpeg)