Follow the Smithsonian Magazine on Instagram at @smithsonianmagazine!

Punch George

Oak Creek, Colorado

They call me “Punch,” is what they call me. I used to help everybody with cows and whatever, you know, punchin’ cows. That’s how I got that name. I think I was about nine when I got that name, and it’s been with me ever since. You come here now, and somebody asks for Otto George—that’s my real name—nobody knows him. It’s always Punch. I was born in Bailey, Colorado, on the other side of the hill, in 1925. I’m eighty-nine, just about ninety. We lived on a ranch over there, but right after I was born they moved up here, to Oak Creek. Course they brought me with ’em. I quit school in the eighth grade. I met my wife in the third grade, and we stayed together all that time.

Andy Maneotis, he was the biggest sheep man around here then. He was a Greek fella. And I worked a lot for him, helping him dock and gather his sheep, till I got a little older. Seemed like the war broke out too soon, or something, and I went right into the service, into the Marines, when I was seventeen, in 1942. They sent me right over there to the South Pacific. I was over there for over three years. Then I come back to the States, and it wasn’t too long after I got back that the war ended. And then I married my wife, the one I met in the third grade. She waited for me, and so we went that route.

Before that, I was working at anything I could get, really. My dad moved to Salt Lake, and I lived here all alone since I was eleven. I lived in an old shack in Oak Creek in an alley, which was all right. But there was no water, no nothin’. And that’s where I lived. You know, I didn’t have no help when he was here, ’cause there was no work then, you know; we’s just comin’ out of the Depression. I can’t say that I remember anything about Christmas or holidays when I was a kid. It was just another day. I guess ’cause I was on my own and there was nobody around, ya know, so I just worked. Everybody burned coal, but a lot of them lived upstairs, and that’s what I done, packed coal upstairs. Get it for ’em and things like that. And I even racked pool balls in a pool hall one time.

We used to go over there to Burns all the time to go rodeoin’. I didn’t rodeo myself. I just

messed around, is all. I never did get good. And besides that, I had too much work I had to do. Just before ya get to Burns Hole, ya start down that steep hill and cross the Colorado River; right on top, before ya start down, is where the rodeo grounds is. We was over there a couple three weeks ago, my daughter and I, and their rodeo grounds is all caved in. A lot of it’s still standin’, but it’s pretty shabby.

I didn’t claim to be a cowboy, but I liked to think I was. I had a lot of horses when we got on the ranch. I liked draft horses awful well. We had around four thousand head of cattle that we loaded on the train, and they hauled ’em to Nebraska, but it took ’em four days to get there. No feed, no water. And when Mom and I got there, we couldn’t recognize our own cattle. They was all ganted up and hungry and dirty and . . . oh, geez, it was terrible.

I never will forget this one time, we was drivin’ our cattle up to Yampa, and they’d all be on

the road, and here’d come the traffic, and this guy come up and couldn’t get through, so I had a guy back there to tell him, “Well, just hang on till we get two or three more cars and I’ll take ya through.” Well, this guy pulled out that big ol’ pistol and said, “We’ll go through right now.” And they took him through. That’s the things that happen to ya, that’s all. Lotta experiences on the ranch.

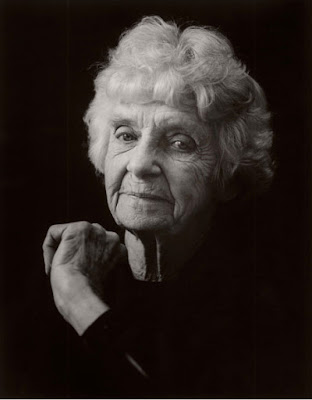

Margie Gates

Burns, Colorado

I was born on Wolcott Divide, and I was a home birth, on November 23 of ’31. I was born in the Depression, of course, and jobs were few and far between. My father had been on the ranch in Radium that his father had homesteaded back in the 1880s, and he had to sell the ranch because his brothers and sisters in California were needing money. This left him kinda without a place to go, so he worked for the McLaughlin family, at State Bridge. He more or less managed the ranch for Mrs. McLaughlin. The ranch was up on the Wolcott Divide, and that’s where I was born. We lived there in a little two-room cabin.

My first memories are from when the McLaughlins decided they were gonna sell that ranch. That meant he had to find another job. So he went to Alma, Colorado, where there were jobs in the Lincoln mine. And I can remember—I was about three years of age—I can remember that the first summer we were there, we lived in a tent. And I remember my daddy making little stools out of a sign, for my brother and I . . . little stools for us to sit on. And I remember the man coming by, looking for his sign! My parents were wonderful. I was a daddy’s girl, and I sat on my daddy’s lap every morning. My mother’s cooking was wonderful. She could always cook meat, whether it was wild meat or whether it was tame. Chicken, pork, turkey, or ham.

My dad leased property up Gypsum Valley, and we lived on what they used to call the Congdon Ranch up there. He leased it, and we did haying and had cattle, milk cows, some sheep. I was just starting high school in Gypsum, and I herded sheep every day, and I learned very early on that you can stay out as late as you want to, but you’re gonna be at the breakfast table, and you are gonna eat breakfast. And then by eight o’clock you had to be out with the sheep, gettin’ ’em up on the mountain to eat for the day. And I’d bring the cows in every night before Daddy got home so he could milk ’em.

I rode every day, and I remember having a runaway. My brother, he wouldn’t saddle my horse for me. He said I had to learn how to saddle my own horse. He was five years older than I was, and he kinda thought he was my boss. Anyway, one day I went out to the corral, and his horse was saddled, and I thought, “I’m gonna ride that horse” rather than saddle my own. So I got on the horse. He saw me get on it, and he said, “Don’t go out the gate. You stay in the corral . . . don’t go out the gate.” Well, what did I do? I went out the gate! And the horse took off. I rode him all the way and finally got him turned around. I was on the main road, and luckily I didn’t run into any vehicle comin’ at us. But I had him stopped and turned around and comin’ back by the time my father and my brother got to me. And I didn’t get spanked!

I married Bud before I got out of nursing school. I met him when he came out to Gypsum to go to high school. I was in elementary and he was in high school. Bud was raised with girls, and so he knew how to talk to girls . . . give ’em a hard time, and all that kinda thing. And he’d walk along the fence there at the school, and we’d all—you know, silly girls—we were all out there lookin’ or doing something. And he was just really nice and smiley and fun to talk to. And I fell in love with him. That’s it. I was twelve. Yeah, I’ve loved him ever since I was twelve. You know, that’s the way it is. And that hasn’t changed.

No comments:

Post a Comment