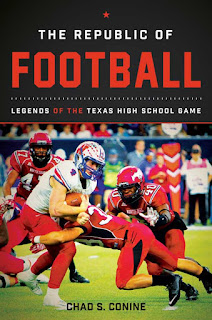

Anywhere football is played, Texas is the force to reckon with. Its powerhouse programs produce some of the best football players in America. In his new book The Republic of Football: Legends of the Texas High School Game, Chad Conine vividly captures Texas’s impact on the game

|

| More info |

Conine, a freelance sports journalist who has written for the Sports Xchange, Reuters, and Golf.com, among others, has been covering Texas high school and college football since the late 1990s. We asked him a couple of questions about the game, about his career writing about football, and some of the controversies surrounding America's most popular sport.

For those who never played high school football or never went to a game, can you tell them what they missed?

I think it’s like anything else, you get out of it what you put into it. If going to high school football games on Friday night is a priority for you, like it has been for me since I was in middle school, then you’re going to spend a lot of ordinary nights at high school football stadiums. But somewhere along the way, you’re going to get caught up in something that’s very exciting, something that can breathe life into a whole community. That’s what the stories in The Republic of Football tell more than anything. They’re all about the magic moments.

What makes high school football in Texas so special?

Building on my answer to the first question, when those lightning-in-a-bottle moments come along, it’s amazing to see how many people get caught up in the excitement of it all. Last December, when we gathered some of the photo and video material for the book, I sat in the stands at NRG Stadium for the Class 6A state title game and looked around at 30,000 people in the stands. That’s pretty amazing for starters. Then I think about some of the playoff games I’ve seen in late November or early December when two teams are playing and the combined enrollment at the schools is around 500 students. But there are 5,000 people in the stands. When they say that the last person to leave town has to turn out all the lights, it’s not really hyperbole.

I was often surprised by how enthusiastically some of the big names responded to talking about their high school days. I’ll tell you one that surprised me in that it redirected my focus for a chapter. I interviewed Cory Redding at the Indianapolis Colts training camp in August of 2014. Cory was going into his 12th NFL season after being a star at Texas and Galena Park North Shore before that. He basically told me to write about Coach David Aymond and what he did at North Shore. I ended up not using much from that interview with Redding, but the chapter is revelatory because of how Aymond changed the culture at North Shore. Redding was intuitive and selfless enough to point me in that direction.

There are risks and rewards with football: kids learn teamwork and how to handle defeat. There are also some serious physical risks. Did your interviews reveal anything about how players, coaches, and families view the risks and rewards?

No. I want to write that without trying to mitigate it in any way because I’ve discovered a huge divide on this issue.

I pay attention to all of the problems that come along with football. I understand and have seen the toll that the sport can take on men who play all the way through to long NFL careers. I know concussions are a huge issue that football is grappling with and I know football has other problems to deal with as well.

But, I can’t recall one time when someone I interviewed for this book mentioned any kind of regret or anything other than absolute enthusiasm for the sport. I think that no matter what problems come along, football people love their sport for everything that it is, and that definitely includes the physical nature of the game.

And here’s the thing that bothers me (about college and NFL football): brutal helmet-to-helmet hits are still being celebrated. It’s not just that they’re not being penalized, they’re still being celebrated. I covered a college game on Saturday night in which a player obviously lowered his helmet to hit a ball carrier in the facemask. The official initially threw a flag, but the review booth determined that it wasn’t a foul because the ball carrier had time to react to the other player.

So the divide is this: football people are making excuses for and dismissing the kinds of helmet-to-helmet hits that other people are saying cause permanent brain damage.

But, understand, I rarely see these kinds of dangerous hits in high school games. They’re the kinds of hits you see when the athleticism and speed increase at the college and pro levels.

Asking the tough questions of coaches and players is an art. What would you say to young writers out there who want to do sports journalism?

I’d tell them that you’re going to piss people off and you’re going to get yelled at. I’ve been yelled at a few times. You have to have thick skin, which can be pretty difficult. But you also have to take risks and write things that you know some people might not like.

The skill, though, is to be thoughtful in the way you ask questions. The words you choose as well as your tone are important. You’re better off asking a tough question after you’ve built up trust with a coach or player, and even then you have to be sympathetic and open-minded. Ultimately, it’s about reading a situation. And when you are yelled at, don’t react in a way that makes things worse.

www.utexaspress.com

No comments:

Post a Comment